Fossil-fuel subsidies are one of the biggest financial barriers hampering the world’s shift to renewable energy sources. Each year, governments around the world pour around half a trillion dollars into artificially lowering the price of fossil fuels — more than triple what renewables receive. This is despite repeated pledges by politicians to end this kind of support, including statements from the G7 and G20 groups of nations.

“I think everyone seems to be basically on the same page that something needs to be done about fossil-fuel subsidies,” says Harro van Asselt, a specialist in climate law and policy at the University of Eastern Finland in Joensuu. “It’s the discrepancy between the rhetoric and the reality that is starting to bite a little bit. We’re figuring out that it’s incredibly challenging to actually make it happen.”

Change is possible. At least 53 countries reformed their fossil-fuel subsidies between 2015 and 2020, according to the Global Subsidies Initiative (GSI), a research group in Geneva, Switzerland. And US President Joe Biden is the latest high-profile politician to vow to eliminate them. But much more needs to be done. “In the next few years, all governments need to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies,” the International Energy Agency (IEA) says in a 2021 report1 laying out a road map to a world with net-zero carbon emissions.

How are fossil fuels subsidized?

Fossil-fuel subsidies generally take two forms. Production subsidies are tax breaks or direct payments that reduce the cost of producing coal, oil or gas. These are common in Western countries and are often influential in locking in infrastructure such as oil pipelines and gas fields, says Bronwen Tucker, an analyst in Edmonton, Canada, at Oil Change International, a non-profit research organization headquartered in Washington DC that works to reveal the costs of fossil fuels.

Consumption subsidies, meanwhile, cut fuel prices for the end user, such as by fixing the price at the petrol pump so that it is less than the market rate. These are more common in lower-income countries — in some, they help people to get clean cooking fuel they couldn’t otherwise afford. In others, such as the Middle East, the subsidies are sometimes regarded as helping citizens to benefit from a country’s endowment of natural resources, says Michael Taylor, an energy analyst in Bonn, Germany, who works at the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), headquartered in Abu Dhabi.

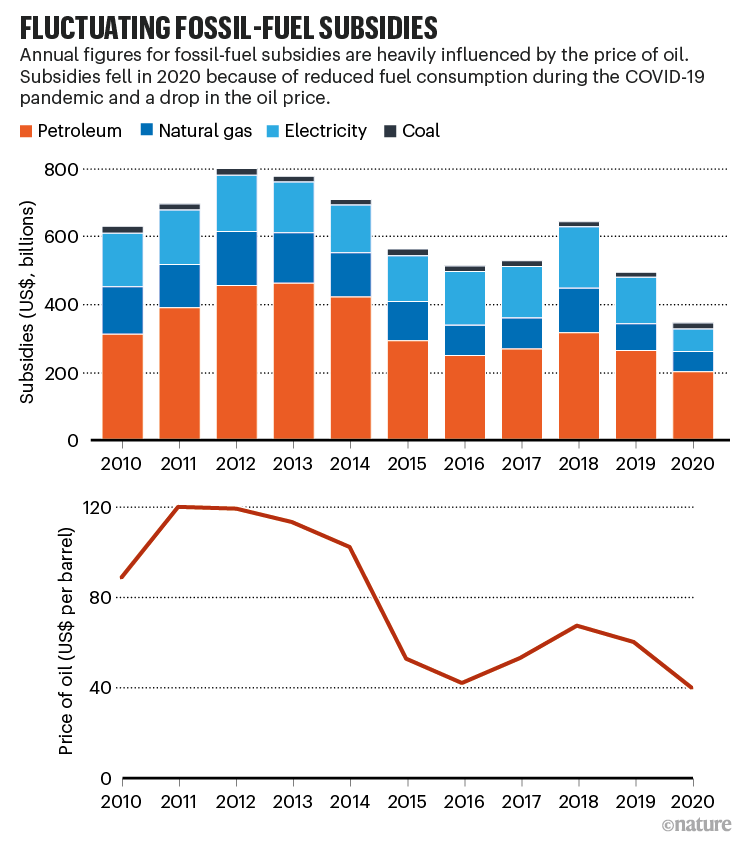

The IEA and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), an intergovernmental body in Paris, estimate that 52 advanced and emerging economies — representing about 90% of global fossil-fuel supplies — gave subsidies worth an average of US$555 billion each year from 2017 to 2019. This dipped to $345 billion in 2020 only because of lower fuel consumption and declining fuel prices during the COVID-19 pandemic (see ‘Fluctuating fossil-fuel subsidies’).

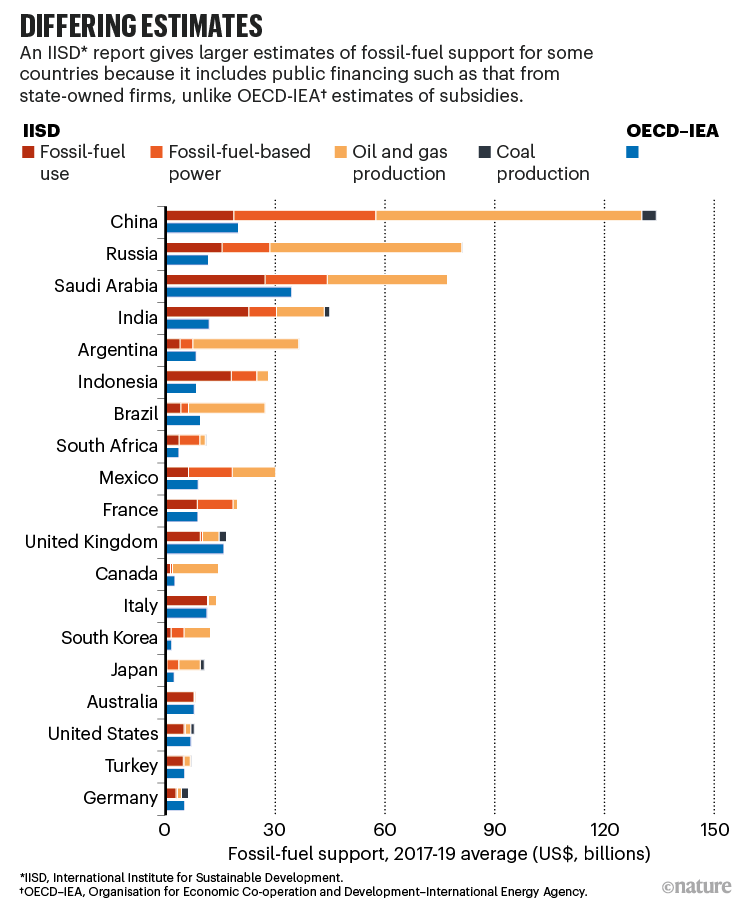

But organizations disagree about how to estimate subsidies. A complication is that some of the public financing of fossil fuels (such as that from state-owned enterprises) mingles both subsidy and non-subsidy elements, points out the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), a non-profit organization in Winnipeg, Canada. In a report published last November2, the IISD incorporates all of this public finance into what it calls “support” for fossil fuels, and estimates that the G20 group of countries alone gave an average of $584 billion per year between 2017 and 2019, higher than the OECD–IEA analysis. The biggest providers of support were listed as China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and India (see ‘Differing estimates’).

Some analysts argue that the hidden costs of fossil fuels — such as their impacts on air pollution and global warming — are, in effect, a kind of subsidy, because polluters are not paying for the damage they cause. Last month, the International Monetary Fund calculated3 total fossil-fuel subsidies in 2020 at $5.9 trillion, or almost 7% of global gross domestic product (GDP), largely as a result of these external costs. But some disagree with this approach. “The damage caused by fossil fuels is massive, but I would not call it a subsidy,” says Johannes Urpelainen, who specializes in energy policy at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies in Washington DC.

Why are they so hard to get rid of?

One problem is definitions. The G7 and G20 countries have vowed to eliminate “inefficient fossil fuel subsidies”, although they haven’t clearly defined what this phrase means. “It’s a very vague commitment,” says Ludovic Subran, chief economist at the multinational insurance firm Allianz, which published a report on eliminating subsidies in May4.

Some countries don’t agree that they have any subsidies to remove. The UK government, for example, says it has none, although the IISD rates it as among the worst of the OECD-member nations, calculating that it gave $16 billion a year to support fossil fuels in 2017–19, on average2. In large part, this is because the United Kingdom forgoes some tax revenue from the use of fossil fuels and directly funds its oil and gas industry. (Other analysts agree with the IISD; a 2019 European Commission report5 came to similar conclusions.)

“They reject the idea that they have any inefficient fossil-fuel subsidies,” says Angela Picciariello, senior research officer in climate and sustainability at the Overseas Development Institute in London. So “it’s quite hard to engage with them on this”. (The UK government did not reply to Nature’s request for comment.) The country did announce in 2020 that it would end support for fossil-fuel energy overseas.

What’s more, each nation has its own reasons for subsidizing fossil fuels, often intertwined with its industrial policies. There are three main barriers to removing production subsidies, Urpelainen says. First, fossil-fuel companies are powerful political groups. Second, there are legitimate concerns about job losses in communities that have few alternative employment options. And third, people often worry that rising energy prices might depress economic growth or trigger inflation.

However, these barriers are surmountable, as some countries have demonstrated. Money not given to fossil-fuel firms can be redistributed to offset the effects of rising energy prices. According to the GSI, the Philippines, Indonesia, Ghana and Morocco each introduced cash transfers and social support, such as education funds and health insurance for poor families, to compensate for the removal of subsidies. Governments also need a plan to help fossil-fuel workers find different employment, adds Subran.

One way to overcome political hesitancy to remove energy subsidies is to maintain support but simply make it contingent on a move to greener energy, Subran says. State-owned enterprises that support fossil fuels can diversify into renewables, adds Picciariello, citing Ørsted, the Danish state enterprise that converted from a fossil-fuel firm into one of the world’s biggest renewable producers.

Periods of low oil prices are generally thought of as good times to remove consumption subsidies, because retail prices can be kept stable. According to the IISD, subsidy reform in India — an oil importer — significantly reduced its support for oil and gas between 2014 and 2019 while taking advantage of low oil prices (see go.nature.com/3ae5uff). (Despite this, the IISD counts overall support in India as rising2, because of growing investments from state-owned enterprises and public financing institutions.)

Low oil prices also helped Saudi Arabia to begin increasing its heavily subsidized domestic fossil-fuel and electricity prices, which are among the cheapest in the world, says Glada Lahn, an environment and energy-resources specialist at the Chatham House policy institute in London. The country has made “significant progress” by gradually increasing fuel prices since 2016, she says. It has cushioned the impacts of the price hikes somewhat by offering cash transfers to lower-income families — although it has now capped fuel prices again to stimulate the economy in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is important that countries are careful to ensure that climate policies don’t hurt the lowest-income communities, notes Tucker: when Ecuador introduced a rapid fuel-tax hike in 2019, widespread protests by citizens prompted the government to reintroduce subsidies. When India decreased its subsidies for liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), it hoped that giving free LPG cylinders to rural populations for use as cooking fuel, a plan it had announced in response to COVID-19, would compensate for higher prices. But it didn’t give them enough, says Vibhuti Garg, a senior energy specialist at the IISD in New Delhi. This means that people instead burn wood and other biofuels — which can ultimately lead to higher carbon emissions.

The GSI highlights Egypt as an example of how to remove subsidies well. In 2013, the country spent around 7% of its GDP on fossil-fuel subsidies, more than its spending on health and education combined, according to a World Bank report6. But then it rolled back the financing, reducing it to 2.7% in the 2016–17 budget. The government communicated with citizens throughout the changes, and used the money to support health and education. However, some commentators said insufficient support was given to poor households.

What effect would reducing subsidies have on climate change?

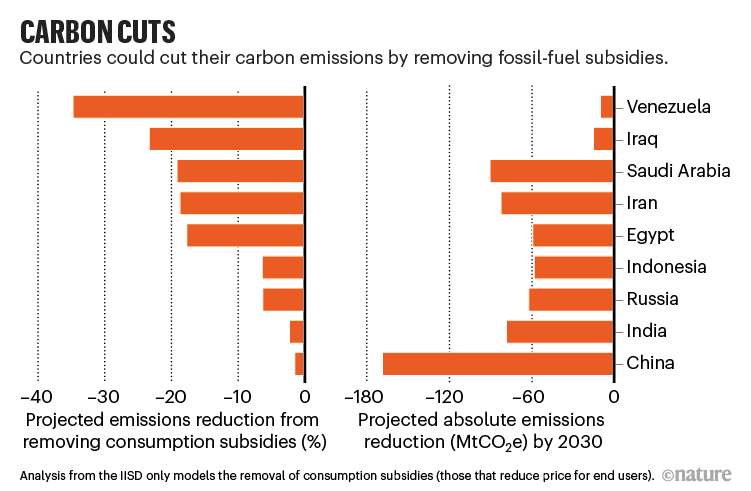

Removing consumption subsidies in 32 countries would cut their greenhouse-gas emissions by an average of 6% by 2025, according to an IISD July report7. This chimes with a 2018 United Nations report8 suggesting that phasing out fossil-fuel support could reduce global emissions by between 1% and 11% from 2020 to 2030, with the largest effect occurring in the Middle East and North Africa (see ‘Carbon cuts’). That reduction could be amplified if the money that would have subsidized fossil fuels was instead used to support renewable energy.

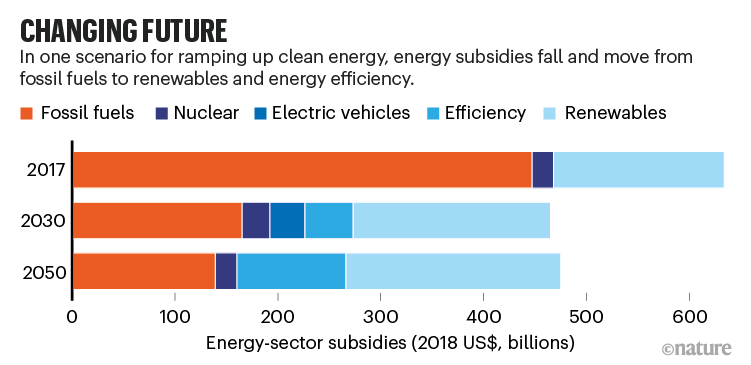

A 2020 report by IRENA9 tracked some $634 billion in energy-sector subsidies in 2020, and found that around 70% went to fossil fuels. Only 20% went to renewable power generation, 6% to biofuels and just over 3% to nuclear. “This overwhelming imbalance of subsidies between fossil fuels and clean energy is a drag on us achieving the Paris climate goals,” says Taylor, who wrote the report. The balance of these numbers varies from year to year, because fossil-fuel subsidies swing around depending largely on the price of oil, he adds.

The IRENA report also mapped out a scenario of how global energy subsidies might change by 2050 to help limit global temperature rises to below 2 °C, compared with pre-industrial levels. It sees subsidies for fossil fuels and renewable electricity falling and moving to renewable energy in transport and buildings, and to energy-efficiency measures (see ‘Changing future’). However, some fossil-fuel support is retained, almost all of which would bolster carbon capture and storage for industrial processes such as cement and steel production.

What are the short-term prospects for reform?

Ahead of November’s COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, UK, the G20’s Italian presidency has said it will push for more progress on phasing out fossil-fuel subsidies. This January, Biden issued an executive order telling federal agencies to cut fossil-fuel subsidies under their direct control. However, legislative approval by Congress would be needed to end most of the tax breaks and financial incentives for the US oil and gas industry.

Meanwhile, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin has said the country will try to be carbon neutral by 2060 — yet its economy is still very dependent on fossil fuels, with plans to develop new oil and gas fields, says Vasily Yablokov, head of climate and energy at the Russia branch of environmental campaigning group Greenpeace, in St Petersburg. "The withdrawal of subsidies would be perceived as a shock that will also affect consumers,” he says.

Some climate advocates also warn against new subsidies to fossil fuels being developed in the name of emissions reductions. Tucker is wary, for example, of subsidies for ‘blue’ hydrogen — a term used for the process in which hydrogen is made from fossil fuels and the carbon dioxide emitted as a by-product is captured and stored. The chair of a leading UK hydrogen industry association quit his post in August, saying fossil-fuel companies were promoting projects that were “not sustainable”, to access billions in taxpayer subsidies.

At the fringes of G20 and G7 summits, groups of small countries have long been working together to try to build a consensus on subsidy reform. An initiative on trade and climate change launched by Costa Rica, Fiji, Iceland, New Zealand and Norway in 2019 aims to set up a member-based agreement in which countries would phase out fossil-fuel subsidies and remove barriers to trade in environmental goods and services. These countries are not the biggest subsidy providers, but this could set a “precedent on developing binding rules on limiting fossil-fuel subsidies, which otherwise do not exist”, says van Asselt.

It’s not enough to phase out only subsidies, says Tucker: ultimately, the goal should be to stop governments giving companies licences to extract fossil fuels altogether. Nevertheless, she’s heartened by the active debates on subsidy reform in countries such as Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom. “Ending subsidies is something that can be won right now,” she says.

"fuel" - Google News

October 20, 2021 at 04:35PM

https://ift.tt/3lXosDl

Why fossil fuel subsidies are so hard to kill - Nature.com

"fuel" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2WjmVcZ

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Why fossil fuel subsidies are so hard to kill - Nature.com"

Post a Comment