When Nikolai Novitsky worked as a supermarket cashier in the southern Russian city of Voronezh, his supervisors made him smash goods near their sell-by date and pour sour cream over the stale bread.

As the rubbish festered behind the shop, Novitsky, 41, was shocked to see elderly women — clearly struggling to survive on their meagre pensions — rummage through it in search of food.

“If you work a full shift, you make Rbs22,000 ($290) a month, and that’s nothing — but it’s still a lot more than minimum wage,” Novitsky told the Financial Times.

While the jailing of opposition activist Alexei Navalny provided the impetus for nationwide protests across Russia over the past two weekends, much of the public anger at president Vladimir Putin’s regime was fuelled by a persistent and growing feeling of economic gloom among the country’s population.

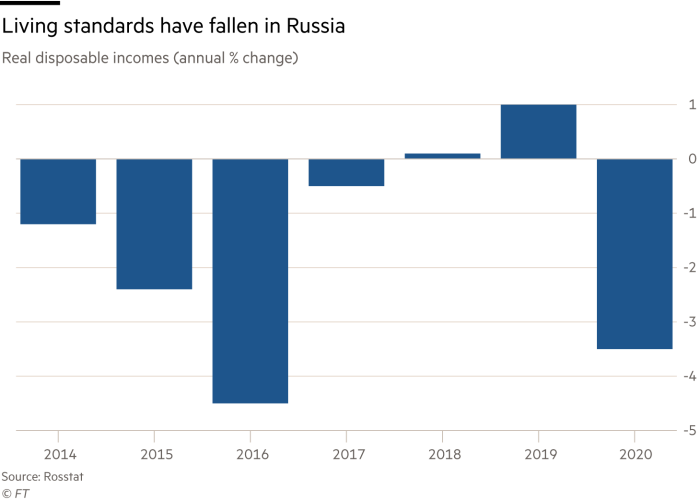

Amid stagnant growth, a collapse in investment and austere spending measures deployed by Putin’s government, Russian real incomes have fallen for five of the past seven years, and fell 3.4 per cent last year. In 2020, the average Russian had 11 per cent less to spend than in 2013.

Much of that economic pain can be traced back to decisions taken inside the Kremlin. The coronavirus pandemic has exposed a failure to tackle longstanding structural problems, such as woefully underfunded hospitals and schools, low pensions and high levels of corruption that typically stops a large proportion of fiscal resources reaching their intended target.

Then, as the pandemic took hold, the government chose to abandon a $360bn investment plan designed to pump funds into poorer regions, and instead doubled down on protecting its $183bn national wealth fund — built up by years of austerity measures such as raising the pension age and increasing retail taxes — as a buffer against potential global shocks.

“People are really at the end of the rope . . . [They] are reaching breaking point,” said Elina Ribakova, deputy chief economist at the Institute of International Finance. “This is the cost of the ‘fortress Russia’ strategy.”

“[The authorities] were so concerned about their external threats that they completely forgot about the domestic population . . . they have been ignored for too long and now they are getting frustrated.”

Household consumption fell 8.6 per cent last year as the economy shrank by more than 3 per cent. While that is less than other emerging markets, it means Russia’s gross domestic product per capita is now 30 per cent lower than in 2013.

Through the first nine months of last year, 19.6m Russians were living below the poverty line, equivalent to 13.3 per cent of the population. In 2018, Putin pledged that by 2024, he would halve the number of Russians living in poverty, defined as living on less than $165 a month. Last year, after the numbers rose, he pushed back that target, and a promise to increase real incomes, to 2030.

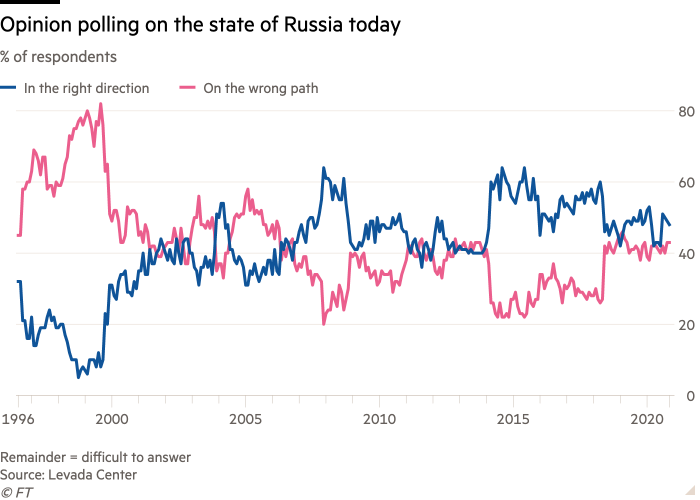

“Economic problems have been the main concern of Russians for many years,” said Denis Volkov, deputy director of the Levada Center, an independent pollster that has surveyed Russian public opinion since 1988. “People complain about low wages and pensions, and high prices for food, medicine, utility rates.”

“At the end of [2020] pessimism started to grow again, and we can expect that [Putin’s] ratings will go down again,” he added.

Putin’s failure to raise Russians’ living standards rankles people like Novitsky. Though his wife’s salary was enough to cover their household expenses while he retrained as an IT technician last year, rapid inflation means the family are struggling to make ends meet while he hunts for a job.

“Obviously Putin doesn’t ride the tram and live in a 20-storey apartment block,” he said. “Maybe he doesn’t know. Maybe they’re lying to him. But all you have to do is go out on the street and you’ll see the truth.”

Such grievances over falling incomes and rising costs have been amplified by claims of regime graft such as those made by Navalny’s team last month, in a video investigation that alleged oligarchs built a $1.3bn palace for Putin on the Black Sea, complete with luxury imported furniture and Italian toilet brushes costing €700 each.

“For 90 per cent of Russians, this toilet brush costs more than they make in a month,” said Sergei Guriev, a professor of economics at Sciences Po in Paris. “You’re outraged — you see the government is promising that incomes will go up, and they don’t.”

“For a few years, Putin has been able to convince Russians that things are not that bad and recovery is just around the corner. But by now, Russians see that he’s lying. There is no recovery, no plan, no vision,” said Guriev, who is a friend of Navalny’s and has advised him in the past. “And on top of that, ordinary citizens and the government officials are not in the same boat.”

Navalny’s activism has not just focused on exposing alleged corruption among the ruling elite. In April, he proposed an economic plan to ease the pressure on Russians, calling for cash handouts of as much as Rbs40,000 per adult, a cancelling of utility bills for the duration of the pandemic and providing Rbs2tn worth of grants to small businesses.

The Kremlin claims its targeted relief programme introduced last spring helped Russia’s economy recover more quickly than western countries with bigger coronavirus aid packages. But the lack of direct payments to citizens combined with the slump in real incomes mean ordinary Russians have yet to see many benefits, Guriev said.

“In absolute numbers, the Russian government has not spent a lot and is going to spend even less in 2021,” he said. “A lot of this spending wasn’t really spending, but deferral of taxes. If you’re supposed to pay this year, you’ll have to pay later. This helps but only temporarily. It’s basically just playing numbers around.”

The sense of feeling poorer has helped drive public support for Putin’s ruling United Russia party to historic lows, according to political analysts. And it is likely to weigh heavily on the party’s prospects in September’s parliamentary elections, where Navalny’s organisation is hoping to tap into rising discontent and use tactical voting to unseat incumbent MPs.

“People are broadly feeling more hopeless and that they have less to lose,” said Ribakova.

“[Russians] disagree with each other on lots of things. But there is a consensus on what they don’t like: corruption, crumbling social safety nets and the ignoring of average people,” she added. “What should scare the authorities is elderly people so angry at the economic situation coming out to protest. That’s the foundation of the Kremlin’s support.”

"fuel" - Google News

February 07, 2021 at 12:00PM

https://ift.tt/3tBm6fa

Rising poverty and falling incomes fuel Russia’s Navalny protests - Financial Times

"fuel" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2WjmVcZ

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Rising poverty and falling incomes fuel Russia’s Navalny protests - Financial Times"

Post a Comment